I am not now, nor have I ever been, a nerd. And yet (you will be surprised to learn) there have been periods in my life when I occasionally exhibited traits that might be described as nerdlike. If you didn’t know me better, the degree in classical accordion and the tweed jacket with elbow patches that I wore every day for a year in my early twenties might have aroused your suspicion. A few people vividly recollect, from my college days, a lush polyester shirt printed with Pre-Raphaelite visions of little girls playing on a beach. (I still say there’s a difference between being a nerd and martyring oneself to art.) Some may remember my seventh-grade parlor trick of reciting pi to forty places, a skill that didn’t impress girls half as much as I thought it would. Throw in a few other peculiarities of my youth — the sci-fi-only reading habits, the mismatched socks, the chilly evenings spent stargazing with my Sears & Roebuck refractor telescope, my mysterious availability for practicing accordion duets on Friday nights — and a pretty damning picture emerges.

I am not now, nor have I ever been, a nerd. And yet (you will be surprised to learn) there have been periods in my life when I occasionally exhibited traits that might be described as nerdlike. If you didn’t know me better, the degree in classical accordion and the tweed jacket with elbow patches that I wore every day for a year in my early twenties might have aroused your suspicion. A few people vividly recollect, from my college days, a lush polyester shirt printed with Pre-Raphaelite visions of little girls playing on a beach. (I still say there’s a difference between being a nerd and martyring oneself to art.) Some may remember my seventh-grade parlor trick of reciting pi to forty places, a skill that didn’t impress girls half as much as I thought it would. Throw in a few other peculiarities of my youth — the sci-fi-only reading habits, the mismatched socks, the chilly evenings spent stargazing with my Sears & Roebuck refractor telescope, my mysterious availability for practicing accordion duets on Friday nights — and a pretty damning picture emerges.

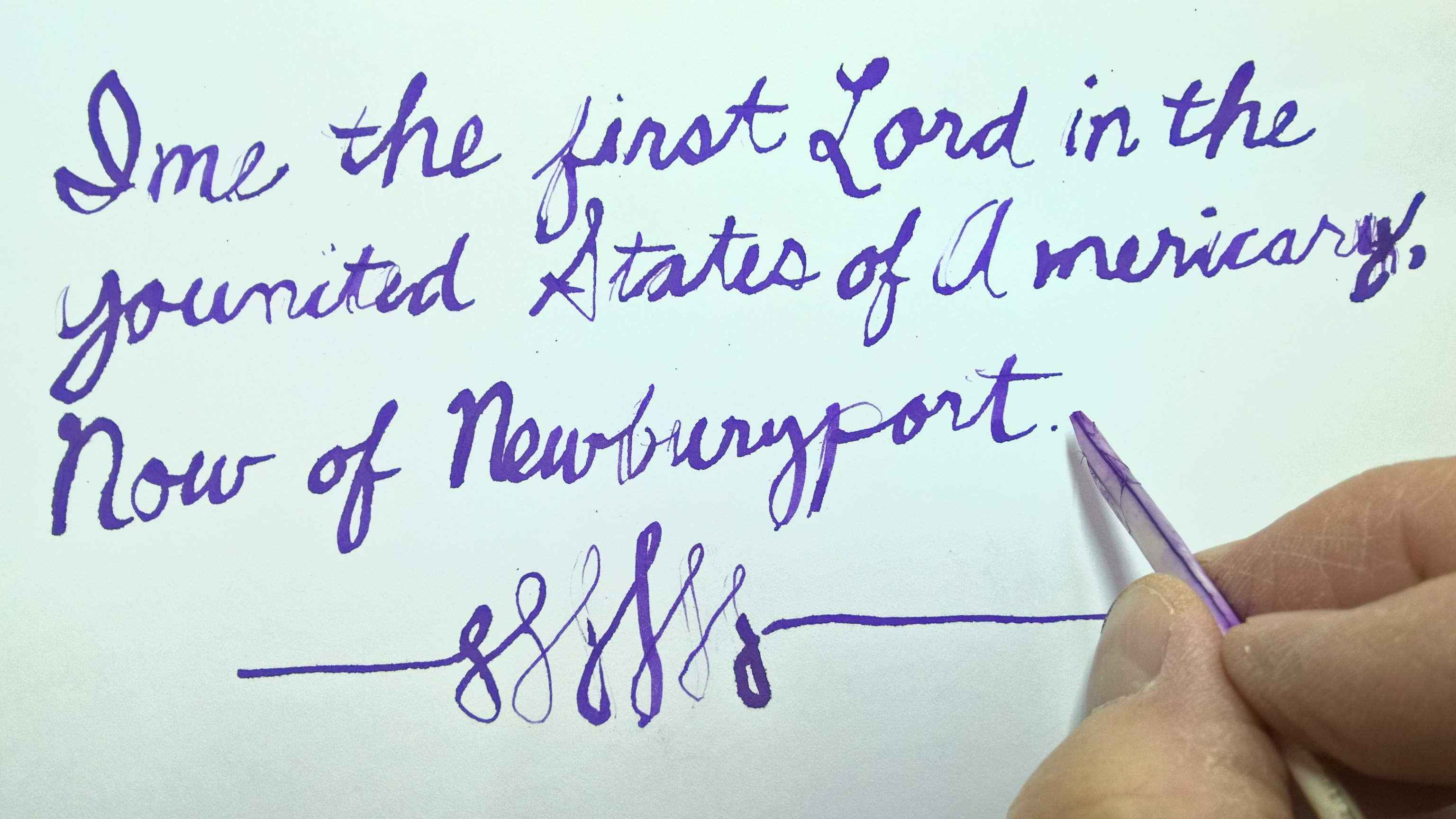

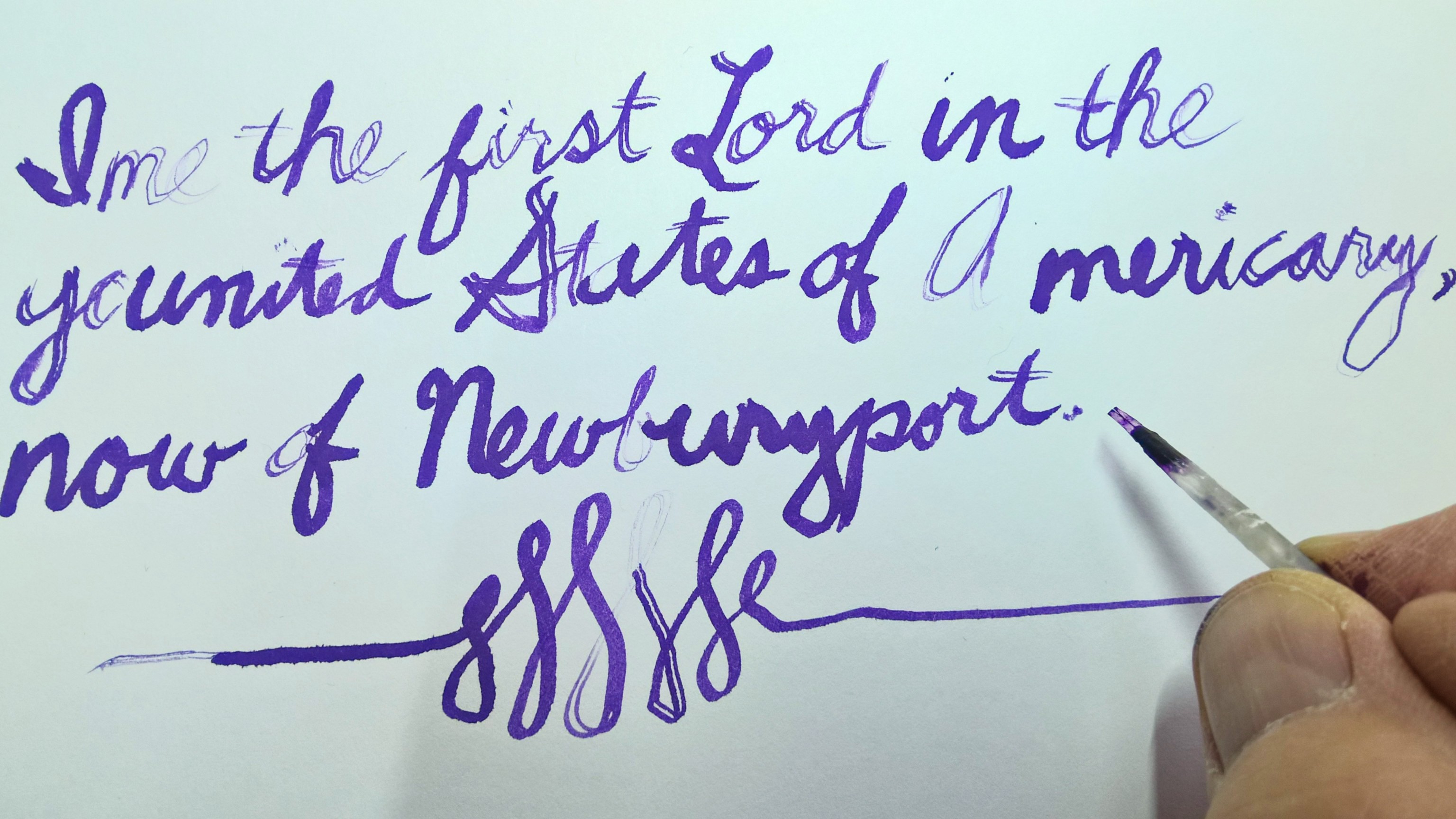

But that’s all behind me now. Anyone who walks past my window today and observes the writer at work, clad in perfectly clean underpants and a neat powdered wig, fashioning pen nibs from eagle feathers and sampling his extensive snuff collection while reciting dialog in made-up accents — all in the service of a very promising work of fiction about misfits in the 18th century — can see at once that I am a model of industry and respectability. The point I wish to emphasize is that I am definitely not a nerd.

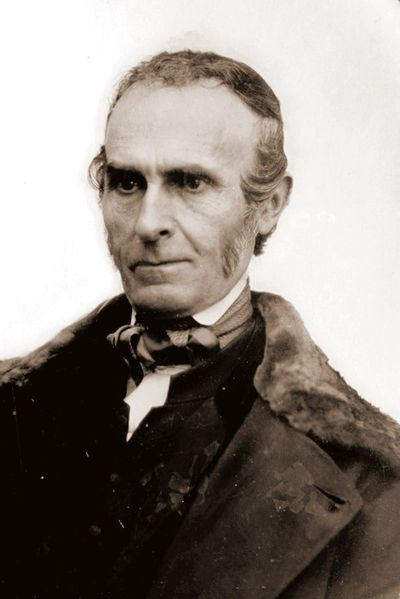

Perhaps because I am so vigilant about guarding against nerdish tendencies in myself, I am quick to spot such traits in others. Even at a distance of more than two centuries, a grim recognition is setting in as I get to know Jonathan Plummer (1761 – 1819). Plummer is the real-life traveling preacher, teacher, healer, peddler, poet, and pamphleteer I’ve cast as the narrator of my stories. Although the term nerd didn’t exist in his time, the personality type certainly did. A nerd, according to my melding of dictionary definitions and personal observation, follows passions and interests that lie outside the mainstream, yearns for intellectual stimulation, pays little attention to what’s fashionable, tends to be socially clueless, may be ungainly and unathletic, and (thanks to the above qualities) is often isolated or ostracized. Jonathan Plummer was all that and more.

Much of what is known about Plummer’s life comes from the eloquent and revealing memoir he published in his mid-thirties. Sketch of the History of the Life and Adventures of Jonathan Plummer, jun. (Written by himself) survives incomplete. Most of his childhood is missing. But he does tell us that as an adolescent growing up in Newbury, Massachusetts, he was bookish and awkward, obsessed with girls but “diffident to an alarming degree” in their company.

‘Vindictive vengeance’

At seventeen, he refused his father’s offer of a hundred acres to farm. He went to work instead as a book peddler for a Boston publisher. This occupation did not make him any more popular, and not just because it was considered slumming. “My reading, traveling, and thirst for knowledge, too,” he wrote, “began to operate to my disadvantage . . . to make me what they called an odd fellow — that is, different from the young fellows who were not readers.” Had he not been a complete nerd, he would have tailored his conversation to suit his company. But Plummer stuck to the topics that interested him. “I was already so insufferably unfashionable as to begin to talk in young company of religion, virtue, poets, philosophers, lords, generals, statesmen, kings, battles, sieges, &c. &c. . . . ,” he wrote. “This made the young people think that I thought myself better than them, and made them resolve to make me feel the torturing effects of their vindictive vengeance.”

What kind of vindictive vengeance? He would receive prank invitations to parties that, when he arrived, turned out not to exist. When he came across female acquaintances walking at night, they would thrust their noses in the air and spurn his offers to see them home. These slights caused him “tortures that no earthly tongue can express.” (Twenty years later, in his memoir, he named the spurners: “Misses Polly Issly, Hannah Moody, Sally Knight, B. Knight, L. H—–n, Dorcas Coffin, three daughters of the late Mr. James Noyes, and Miss Elcy Tucker.”)

Like many nerds, he talked funny. And the more learning he acquired from “company and books” (said company including a number of Harvard- and Dartmouth-educated preachers who had impressed him), the funnier he talked. In his brief career as a nomadic schoolmaster in New Hampshire, some people doubted he had even been born in America, so posh were his accent and diction. His father was not impressed. “He had always supposed,” the son wrote, “that I was a fool, treated me as such, and was now altogether unwilling to suppose the alteration which he perceived in my discourse [was] produced from anything but a want of brains.” I imagine Plummer speaking with a sort of Boston Brahmin, echt-Harvardian, Rev. Peter Gomes-ish accent.

Plummer had his own pet theories about God and the universe. He believed that millions of other planets were inhabited, for example — which led him to the lonely supposition that God was too busy dealing with extraterrestrials to care about mere earthlings. He later backed away from that position. God does communicate with people, he concluded — even with “such a worm, such an insect” as Jonathan Plummer — but does so through dreams. Plummer would expound on his “science of dreaming” to anyone who would listen. “I often continued my discourse on dreams after people told me to my face, in plain words, that I was crazy,” he wrote. No doubt his horrendous breath, brought on by the head-rotting sinus condition known as catarrh, only increased their eagerness to shut him up.

‘A form of insanity’

His loud singing and humming got on everyone’s nerves. In one New Hampshire school district, officials declared the habit to be grounds for dismissal. “Finding that I sung a great number of songs and tunes in my apartment alone, they concluded that I was insane,” he wrote. It’s a form of insanity I happen to share, but as you probably know, I’m even fonder of whistling. I think I will make Jonathan Plummer a whistler from now on.

He went through all the usual nerd agonies over what to do for a living. Too poor to continue teaching and too scholarly for any practical occupation, he seemed to be a man without a niche. He worked as a scullion — a lackey and boot cleaner — in a tavern until he was told, “We’ve found a better Negroe than you.” His landlady, a doctor’s wife, taught him weaving, but he became distracted by the husband’s medical library, which he devoured volume by volume. Amazingly, that was all the training he needed to find “some practice as a physician,” albeit not a very lucrative practice.

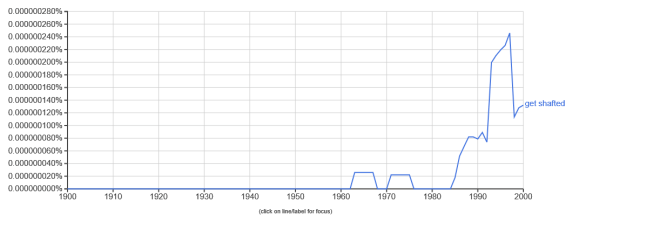

To survive, he engaged in what modern business gurus call “multipreneuring” but in those days was just a bunch of shitty jobs. He listed them: “Farming, repeating select passages from authors, selling holibut [an old spelling], sawing wood, selling books, ballads, and fruit in the streets, serving as a porter and post-boy [newspaper deliverer], filling beds with straw and wheeling them to the owners thereof, collecting rags, &c. &c.”

It was during this desperate period, the 1790s, that Plummer was rescued by Lord Timothy Dexter of Newburyport. Lord Dexter (1747 – 1806) — my stories’ protagonist — came from nothing and made a fortune through imaginative business deals such as exporting mittens, warming-pans, and stray cats to the West Indies. His speculations seemed harebrained but always worked out in his favor.

Lord Dexter was a generous soul, particularly when sober. Recognizing Plummer’s gifts but also his need, Dexter offered to set him up as either a physician or a preacher, whichever he preferred. Plummer couldn’t see specializing. But he did accept the post of Poet Laureate to Lord Dexter. The job, which paid him a small stipend for several years, was probably Dexter’s way of extending a bit of charity while preserving Plummer’s dignity. It required little of Plummer other than that he recite the occasional ode to his patron (“More precious far than gold that’s pure, / Lord Dexter shines forevermore”) in Market Square while wearing a star-studded black uniform (about which more later).

‘Died a virgin’

Plummer never outgrew his nerdy ways. I don’t believe he ever achieved — or sought — contentment or a sense of belonging. He never found a mate, despite his frequent marriage proposals to virtual strangers (including eight rich widows in the space of two impassioned months). He apparently died a virgin.

But in his last two decades he did acquire a certain gravitas. Traveling around New England, he managed to fuse his assorted talents into a single, spellbinding act: a combination of preaching sermons, which he delivered with great theatricality in his sonorous voice; reciting or singing topical ballads, often made up on the spot; and opening up his basket of sundry goods — medicines, toiletries, sewing notions, and his own broadsides (articles printed on a single large sheet) about the latest murders and disasters. Then as now, if it bled it led.

In a subsequent post, I’ll let John Greenleaf Whittier (1807 – 1892), the Quaker poet, describe the wonder he felt as a child whenever Plummer stopped in the town of Haverhill, Massachusetts.

I find Jonathan Plummer fascinating, and not just because he embodies a type that is well known to me. He was also completely original — sincere, passionate, vulnerable, candid to a fault, and ascetic beyond hope of self-preservation (a sad subject for another post).

I’m going to hand over the sign-off to somebody who can do a better job of summing up Jonathan Plummer than I can. Henry S. Ellenwood (1790 – 1833), a distinguished poet, pedagogue, and educational reformer from Newburyport, was well acquainted with the man. On Plummer’s death, in 1819, Ellenwood published a rollicking, witty poem (which I’ll post someday) called “Elegy and Eulogy, and Epitaph, of That Famous Poet, Mr. Jonathan Plummer.” He introduced the work with this biographical note:

[T]he character of Jonathan was, as far as I know, irreproachable in every particular. He was most scrupulously conscientious; flattered nobody; cared for nobody; was seldom long in a place; and, with as unaffected an independence as ever was known, despised all the fashions of this world, and minded his own business. I wish it were in my power to say so much in favor of any other person upon earth.

Mr. Ellenwood may have been among the few to locate the human being within the nerd.